LLM assisted coding - a waste of energy?

Overview

In this article I compare the time and energy cost required to update a simple old code used to generate entropy from a RTL SDR dongle from C to C++ by hand and using LLM-assisted coding (LLMAC). The addition of Boost's program options library is considered an extra and will prove to be an issue.

The long-and-short of it is that running a model and coding agent locally did not reduce the time required to port the code and therefore did not reduce the energy required, either. Worse than that, the use of LLMAC resulted in a significant increase in the runtime to solution and at least a 1.5x increase in required energy from at most 476.9 [Wh] to 1070 [Wh].

How to read

For those interested only in the results I suggest having a look at the experiment, the summary of the code analysis and the conclusions and possibly at my subjective observations.

Those more interested in the specifics are welcome to read the brief summaries in each of the subsections of Update (tool-assisted).

The reason for doing this is detailed in Introduction & Motivation and the process as well as the results of each step are described in Analysis phase (Manual), Update (Manual) and Update (tool-assisted).

Introduction & Motivation

I've had my reservations regarding vibe coding. In part because this pathway to software development does not demonstrate that the user possesses the technical and mental skills necessary to develop software. In part it was due to the assumption that the tools require a permanent connection to the resp. provider (e.g. OpenAI) and therefore will require the code to be shared with the provider.

A simple agentic coding attempt is not in itself noteworthy or interesting, thus I set out to see whether LLM-assisted coding (LLMAC) can perform a simple task effectively and efficiently, especially considering its heightened energy requirements.

My main hypothesis was that while LLMAC could cut down on the time to solution it will consume vastly more energy for an identical outcome than if the task was accomplished by a human only.

My history with LLMAC

Having stumbled upon LM Studio (LMS) sometime in September of 2025 and then seen an article on vibe coding with LMS and Crush in iX 12/2025 I thought that it is time to try the tools instead of rejecting them on principle.

I was initially sceptical whether the desired result can be achieved at all, given that the first attempt at vibe coding by following the article and using Crush and LMS failed spectacularly! The article was a mess as it wholly lacked any sort of proper explanation for the inclusion of MCPs, LSPs or, more critically: the definition of the model parameters such as context_window and default_max_tokens for Crush - almost as if it were written by a LLM. After getting Crush to actually communicate with LMS by using ChatML as a prompt template the results were extremely disappointing. Running /init on the sample project of the article yielded a bunch of wild hallucinations! For a project consisting only of a single Python application file the "analysis" claimed the project to be a Go project or a C++ project (depending on the run) and claimed formatting rules exist within the repository. There were none!

This disappointment and a wasted 3 hours put me off of "vibe coding" for quite some time. More recently I saw OpenCode advertised by https://openalternative.co/ on BlueSky. This agentic coding tool seemed well-organised, with proper documentation and - most importantly - a complete absence of cringy soundbites that were present in the sparse documentation of Crush. This seemed like a good time to try my hand at a port of rtl-entropy from C to C++, with the goal of future improvements.

Why spend time duplicating work?

I like writing the documentation of my code first and then filling in the skeleton of comments with functional code. That is, unfortunately, not the rule and one often finds old code that is poorly documented and potentially in a language that is considered "archaic". It's often advertised that coding agents will simplify documentation and porting of code bases. For instance one of the declared aims of DOGE was to move the entirety of the code used by the social security administration of the US away from the "archaic" COBOL. This, they claimed, was to be accomplished using AI.

- Energy cost of using LLM assistants is hard to come by

- Claims of time gain appear overblown and are not substantiated by numbers

- Hard data is generally not readily available

A claim often raised is that LLM coding agents will reduce the time spent on "boring" everyday work like writing tests or documentation, freeing the developers to do creative work and not spend time learning any particular language's syntax.

Remarkably absent from various articles are hard numbers. Claims of a ten-fold speed up of complex tasks get thrown around without providing a specific example where such actions have been accomplished, resulting in estimates using proxy metrics that swing all the way from a gain into a loss. Worse still, the energy required is almost never raised in the same article that praises the use of the tools.

Some opinion pieces do consider the energy cost of using LLMs in general, but at a per-query granularity. This is a metric that could be useful as a starting point for an academic analysis, but not readily digestible. Further such blog posts fail to provide primary sources for the numbers they do use, along with intermingling various metrics (e.g. energy and \(CO_2\) equivalent emissions). Or they adopt the numbers provided by the companies whose business model is reliant on a widespread use of the technology.

Some of these companies have provided blog posts presenting their analyses of environmental impacts. Notwithstanding the fact that those numbers are provided in an informal fashion by an entity that has a vested interest in appearing sustainable the published information generally lacks hard values regarding energy use. Tech companies are in fact so clam on this information that people had to resort to estimates by proxy to determine roughly how much energy is being consumed for a query.

A notable example of a somewhat practical estimation of the energy use of agentic coding is this blog post by Simon Couch. The author estimates the energy cost of his median coding session using Claude Code by way of estimating the energy required per token and scaling the obtained value with the number of tokens used. The blog post suggests that a median day of agentic coding for the author results in around 1.3 [kWh] of electrical energy consumed. Unfortunately, even this digestible example relies heavily on estimating the energy used by a model running on hardware hosted by a third party.

Further, exporting the inference step to an external service is a prime example of externalizing costs, while also opening oneself up to potential liability due to data leakage. The latter is especially true for proprietary code, generally a prime example of legacy code that is supposedly a great target for LLM-assisted optimisation and porting to newer languages and frameworks.

To introduce a bit more clarity into the entire discussion I provide here the analysis of a smiple task accomplished by hand and using a local LLM and compare the time required to accomplish the task as well as the overall electrical energy consumed while doing so.

The Experiment

In my recent work I compared random number generators (RNGs) of the pseudo- and quantum variety. To make the comparison a bit more interesting we also tried getting something akin to a hardware true random number generator (HWTRNG). This was done using a software-defined radio (RTL SDR v.3) and rtl-entropy . Note that this does not exactly give us a HWTRNG, since the code itself just feeds radio entropy to the RNG daemon in linux, which then makes it accessible via /dev/random for a simulation to use.

The rtl-entropy code still works, but it has been declared abandoned in 2020 and is painfully slow ( \( \sim 17\times\) slower than Mersenne Twister PRNG). I've been thinking that an update or rewrite would be good and now that I unfortunately have the time may as well try it! A quick glance at the repository tells us that the code is in C, whereas my main programming languages are C++ and python.

Thus the stated goal of this project is to port the existing code from C to C++ and remove all bits that are unnecessary to use it with the RTL SDR dongle on a Linux machine. All without impacting the functionality of the code.

As an addendum, after a brief glance at the code, introduction of Boot's program options library to parse a configuration file and options passed to the software on the command line. At the end of the day I want an updated version of the tool that will run identically to the previous one.

The comparison between myself and myself with OpenCode will thus focus on:

- Time needed to switch the source to be compiled and working with a C++ compiler without necessarily rewriting the code to be C++ (or ++C).

- Time required to replace user input parsing and the help menu using Boost program options.

- Power draw history of the respective rewrite attempt

- Overall energy required to rewrite the code for each of the above three stages.

The project should be suitable for an effective and efficient use of an LLM since it is not so much about generating new code that I do not understand as about converting existing code from one language (C) to a closely related language (C++) to facilitate future development. The code base is sufficiently small to not be a strain on my limited machine resources. The results of the changes are documented in the branches of my fork of the repository.

One hypothesis derived from the testing phase of OpenCode with LM Studio using the "Qwen3 coder 30B" model suggests that a manual rewrite may not only be faster, but far more energy efficient since the LLM-based approach tends to get stuck in infinite loops.

To avoid biasing the manual rewrite of the code I shall start with it and build an understanding of the code base manually first. This will necessarily bias the following rewrite using LLM tools but I consider this acceptable as it is my belief that no sane person would attempt to rewrite a code-base they do not understand using LLM tools. Furthermore, the rewrite using a local LLM requires more guidance than a large-scale model due to constrained resources on the machine.

The System

The system this test was run on is as follows:

- CPU: Ryzen 7 5800 X3D

- GPU: RTX 3060 w. 12 GiB of GDDR6 VRAM.

- RAM: 64 GiB DDR4

- OS: OpenSuSe 15.3, Kernel 5.3.18

- NV driver: 550.90.07

- CUDA 12.4

- LM Studio: 0.3.37

- OpenCode: 1.1.39

The system is connected to a WiZ switchable socket that reports the power draw of the system and its peripheries to HomeAssistant, which in turn stores it to an Influx database. Additionally an integration of the power over time is performed in HA via a left Riemann sum to obtain a value of the electrical energy consumed to date.

The system is equipped with 2 24" monitors running at a calibrated brightness and colour scheme, each consuming a fixed amount of 22 W. Thus 44 W of the system's power draw are accounted for solely by the monitors. They are two very remarkable energy sinks!

Analysis phase (Manual)

The manual inspection and analysis of the code base required 72 minutes but could be accomplished much faster if done in a more focused way. Below are the observations collected during this phase.

Top-level view

A quick check of the contents of the repository suggest a TravisCI test setup (.travis.yml). Alas it only tests whether the code can be compiled and performs no further checks. Thus there are apparently no proper checks of functionality of the code that could be used to ensure that the changes do not affect function.

The .1 file is the man-pages entry for the software and .pc.in is the pkg-config template for the project both can be ignored as they do not affect the source code and the program.

The README informs us that the project is abandoned and ChaosKey or OneRNG should be used instead. In a twist of fate the functionality of this project has outlived the availability of both suggested alternatives!

According to the README the code performs the following actions:

It samples atmospheric noise, does Von-Neumann debiasing, runs it through the FIPS 140-2 tests, then optionally (

-e) does Kaminsky debiasing if it passes the FIPS tests, then writes to the output. It can be run as a Daemon which by default writes to a FIFO, which can be read byrngdto add entropy to the system pool.

Thus we expect the code to draw signal samples from the RTL SDR dongle and run them through von Neumann de-biasing, then through FIPS 140-2 tests and write them to an output. It is unclear from the documentation whether passing the FIPS tests is a prerequisite to writing to the output or just to running the optional Kaminsky de-biasing. The Kaminsky de-biasing step is optional and utilises the bits rejected by the von Neumann step, computes a SHA512 hash from them and encrypts the entropy from the v.Neumann filter using this hash as the key.

The requirements for building the software are inferred from CMakeLists.txt of the minimalist CMake build process is used in the project:

- RTL-SDR libraries

- libcap-dev

- openssl (libssl-dev)

- pkg-config

The program provides a help menu, to be invoked via rtl_entropy -h which we will want to port to use Boost program options.

Build process

The build process uses CMake, as indicated by the presence of CMakeLists.txt in the top-level directory and in src/. Further, the minimum version of CMake required by the build process is 2.6. (l 39) and we further see that the project is written in C (l. 40).

Additional CMake modules are loaded from the ./cmake/Modules directory. These are used for versioning and to find various libraries required for the project.

By default the project builds in the Release configuration and the version of the package is 0.1.2.

If the compiler is GCC or CLANG the following options are added to the compilation:

1-Wall -Wextra -Wno-unused-parameter -Wsign-compare -pedantic -fvisibility=hidden -fvisibility-inlines-hidden

where the latter 2 are generally included because we assume here Linux as the platform of choice.

Packages pkg-config,librtlsdr,libbladerf,openssl,libcap are loaded via CMake (ll. 91 ff). Here LibCAP is loaded only if we're not on FreeBSD or Darwin (macOS) and the path to OpenSSL is hard-coded for macOS.

OpenSSL and LibRTL-SDR include directories are added to the projects include directories (l. 108-111) and similarly their library directories (l. 120-123). LibCAP directories are added in a similar fashion but guarded by IF statements testing whether we are not on FreeBSD or Darwin (macOS).

The source files are stored in the src directory, which is added via add_subdirectory(src) in line 132.

An uninstall target and Pkg config are set up in l .137 - 166 *and are of no further interest to us at this moment.

Overall the top-level CMakeLists.txt is responsible for the build environment set-up and actual build source definitions are provided in src/CMakeLists.txt.

The source files fips.c fips.h log.c log.h util.c util.h are to be compiled into a library, rtlentropylib (l. 1, 3)

The executable rtl_entropy is compiled from the rtl_entropy.c source and linked with rtlentropylib, OpenSSL, LibCAP and LibRTL-SDR libraries. It is then set as install target.

The installation step is configured in l. 24-28, installing rtl_entropy as binary and rtlenropylib as library.

An additional executable target is defined for BladeRF if the library is present and both RTL and BladeRF executables are set as installation targets if both are present in the system.

Files

Our first analysis of the build process indicates that only 7 source files are relevant. We further analyse the code for additional inclusions

- util.h: Requires only

evp.handsha.hofopenssl. - util.c: Includes

log.handutil.has well asdefines.hand other system libraries (signal, math, unistd, grp, pwd) and OpenSSL headersevp.h, aes.h. - log.h Includes only

syslog.hfor system logging services - log.c includes

log.handdefines.has well as additional system headers - fips.h: requires no includes

- fips.c includes

fips.hand standard system libraries. - rtl_entropy.c includes

defines.hlog.hutil.hfips.hrtl-sdr.hand other standard system libraries, with compile guards for Apple and FreeBSD

Conclusion: The FIPS tests used are actually re-implemented in the code, rather than requiring an external library!

Overall set of files: fips.{c,h}, log.{c,h}, util.{c,h}, defines.h, rtl_entropy.h

Files that can be removed:

brf_entropy.csrc/junk/brf2.ccmake/Modules/FindLibbladeRF.cmake

Source code

Consider the main source file of the software: rtl_entropy.c

Therein we observe that the functions usage, parse_args and read_config_file (l. 112 - 322) are used to provide a help menu and option selection to the user and allow the user to provide an options file instead of specifying everything on the command line.

This can be easily replaced using boost_program_options and should therefore be moved to a separate file.

The important code is located in lines 519-727 of the file. The preceding lines are, to a part, bookkeeping and can be significantly abridged using the aforementioned Boost library.

Summary

- Since we are interested solely in running this on a Linux system all logic involving FreeBSD or Darwin (macOS) can be removed

- Our goal is to have an up-to-date code base working with the RTL-SDR dongle. As such all dependencies on BladeRF can be removed. Thankfully the CMake files show us that this can be done trivially since BladeRF code is confined solely to its own

brf_entropy.csource file. - The set of relevant source files is thus:

fips.handfips.c- Core FIPS logic.log.handlog.c- Assumed logging functionsutil.handutil.c- Assumed utility functionsrtl_entropy.c- the main loop of the project.

- Files that can be removed

brf_entropy.csrc/junk/brf2.ccmake/Modules/FindLibbladeRF.cmake

- Help, and user input are handled via

usage,parse_argsandread_config_file. These functions are thus to be replaced using Boost. - The main program logic is located in lines 519 - 727 of

rtl_entropy.c

2 will not affect the build process and can be trivially accomplished. Overall the time required to read through the code and build process was 72 minutes, with the system running at a constant 131.5 [W]. This is equivalent to a total of 157.8 [Wh] of energy consumed just for the analysis phase!

Modification plan

Given the observations made above and the aim of this project being specifically on RTL entropy the following changes shall be made:

- Remove BladeRF dependencies from the build process, as well as

brf_entropy.cand the corresponding CMake file from the source. - Remove the ability to compile the source on FreeBSD and Apple systems by removing the conditions from the build process and the preprocessor guards from the code. Up until this point the source code remains in C and only the build environment is modified slightly.

- Convert the project to C++ and rename all source files to

.cpp. - Introduce

extern "C"to the source where needed s.t. it can be compiled with a C++ compiler. - Move the argument parsing to

argparse.{h,c}and use Boost program options library.

The minimum requirement to declare the update a success will therefore be achievement of 4 and consist of cleaning up the code and build files, the update of the source to C++ and achieving compilation with a C++ compiler.

After spending 72 minutes exploring the repository and the code, with a few distractions along the way, the gut feeling indicated that an update to C++ should be doable within 3 or 4 hours. Accounting for an optimistic estimate we add 1/3 of the estimated time as buffer for a total estimate of ~4-5 hours. An afternoon's worth of work, thus!

Update (Manual)

| Task | Duration [min] | Power [W] | Energy [Wh] | "Idle" power [W] | Excess energy [Wh] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remove BladeRF & extra architectures | 14 | 135.79 | 31.68 | 135 | < 1 |

| Convert the project to use C++ compiler | 46 | 135.79 | 104.11 | 135 W | <1 |

Introduce Boost's program_options |

88 | 125 | 183.3 | 124 W | 1.5 |

Clean-up

Removal of the BladeRF dependencies is a simple task of deleting the files and corresponding lines from CMakeLists.txt. Because of its simplicity I tackle the removal of the FreeBSD/macOS handling in parallel and both tasks are accomplished in 14 minutes of manual editing using Vim.

Testing with GCC 14.3.0 reveals that the 2nd argument of rtlsdr_get_device_usb_strings (l. 532 of rtl_entropy.c) will fail with an error, while the older GCC 11 just throws a warning here.

I thus revert to using GCC 11 (the system's default) for the current stage of development and earmark the creation of meaningful tests for the future. Specifically add the introduction of unit and integration tests using Catch2 to the ToDo list.

During the 14 minutes required for this task the system consumed a total of 31.68 [Wh] of energy. Of these we can apportion less than 1 [Wh] to the actual modification.

Updating to C++

A simple change of the project language from C to CXX in CMakeLists.txt will not suffice as the build project will fail with Cannot determine link language for target "librtlentropy". This is unsurprising as all source files are in C and ignored by the build process. Renaming all sources to .cpp and updating the file endings in src/CMakeLists.txt allows the compilation process to progress until it meets the calls to malloc.

While C allows us to assign the void pointer returned by malloc to a pointer of a different type implicitly, C++ does not. Hence each call to malloc in the source must be prefaced with a static_cast to the appropriate pointer type. Besides these changes the types of the variables manufacturer, product, serial in l. 510 of rtl_entropy.cpp need to be changed from char* to char since these are fixed-size arrays and the name of the array is a pointer to its beginning. Otherwise g++ will complain about passing a double pointer.

In summary, to convert the project from C to C++ (or rather ++C) we need to:

CMakeLists.txt: Change project type toCXX, setCMAKE_CXX_EXTENSIONStoON,CMAKE_CXX_STANDARDto11and addenable_language(CXX)for good measure.- In

src/CMakeLists.txtrename all source files to.cpp - Rename all source files from

.cto.cpp - Add

static_cast<ptrType>()to eachmalloccall in the code inutil.cppandrtl_entropy.cpp - Change the type of

manufacturer, product, serialin l. 510 ofrtl_entropy.cppfromchar*tochar.

At this point the code will compile and run correctly when tested using the commands proposed in the README:

1./rtl_entropy -s 2.4M -f 101.5M | rngtest -c 1280 -p > high_entropy.bin

The update to C++ required overall 46 minutes and proceeded without major impediments. For the entirety of the time, right until the testing phase at the very end, the rewrite proceeded in parallel with a Monte Carlo simulation that was running in the background. The latter resulted in the higher than normal power draw of the system. Ignoring this artificial increase the energy required for this phase is 104.11 [Wh]. Since text inputs and 5 compilation attempts do not raise the power draw of the system sufficiently for the 1 W resolution of the socket to pick it up we can conclude that the the actual energy cost of this step is below 1 [Wh].

Introducing Boost

The next goal is to eliminate the functions usage, parse_args, read_config_file from the main file of the project. They shall be replaced by a function prog_opt_init that will utilise Boost program options to read the options either from the command line or a file.

Since the latter function has been a staple of my code since I first started using it in 2014 I will be reusing the implementation from the RandNumSourcesInMCSim code.

This approach requires the definition of a struct to store parameters to. This is implemented in argparse.h with additional Doxygen documentation of the parameters. The definition of the function uses the default values of some of the global variables provided in rtl_entropy.cpp as default value arguments for Boost. The configuration file is now set by convention to configuration.txt and will be read if present, with options specified in the file supplementing but not replacing command line arguments. Option parsing from file or command line is thus now done in two lines in the main function. Because special values of GID, UID and filenames (here: NULL) are used in the C code to indicate that no value has been provided by the user and a default behaviour should be triggered I replace the default values of the corresponding string variables by an empty string and test for an empty string in main prior to using those variables.

The parameter struct is thus manually unpacked into the global variables in main with appropriate type casts.

Overall this adds 104 lines of code and comments in argparse.{h,cpp} and 32 in rtl_entroy.cpp, while removing 271 lines from the latter for a total reduction of 135 lines of code.

The entire process to introduce Boost program options and ensure that the code compiles and runs appropriately required ~ 88 minutes of mildly focused work. For the entirety of the time the system is idling at ~125 [W] and thus the total amount of energy used is 183.3 [Wh]. Of these the actual process of modifying, compiling and testing the code required approximately 1.5 [Wh].

Summary & Conclusion

Starting from scratch with a code not yet seen except for the file endings, which indicated that the programming language of choice of this project was C, and a goal of porting it to C++ it took me 220 minutes, or 3.67 hours to achieve all of the goals. The minimum requirements were met within 132 minutes (2.2 h).

The individual start and stop times are given in the table:

| Task | Start | Stop | Power | Energy | Idle power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | 11:17 | 12:29 | 131.5 W | 157.8 | 131 W |

| Remove BladeRF and extra arch | 14:33 | 14:47 | 135.79 W | 31.68 | 135 W |

| Convert the project to use C++ compiler | 10:13 | 10:59 | 135.79 W | 104.11 | 135 W |

Introduce Boost's program_options |

13:50 | 15:18 | 125 W | 183.3 | 124 W |

The idle power in each case is dictated to a large part by the two monitors and the system running a Monte Carlo simulation using half of the available cores in the background.

This results in a total energy use of \(476.89 [Wh]\), which covers the entire process from analysing the repository and code to changing the code to C++ and using Boost to simplify command line argument processing.

This view of the energy cost is rather uncharitable since it attributes all of the energy used by the system to the modification process rather than the simulation running in the background. Since the base/idle power draw is identical to the power draw during the editing process one could be tempted to attribute no cost to the rewrite. This is, of course, false, but the resolution of the power plug does not allow us to differentiate editing from the normal execution process. The plug seems to respond only to changes in power draw > 1 W. Thus, since no difference can be observed I'm estimating that the editing process consumed at most roughly 3.67 [Wh] of energy.

Update (tool-assisted)

As noted in the experiment I am using OpenCode and LM Studio, running Qwen3 coder 30B model in Q4_K_M quantisation locally on the RTX 3060 and the CPU in parallel. The CPU remains under the powersave governor, whereas the GPU is in its default state with a power limit of 170 W.

To reiterate, the goal is to analyse the code, determine its main language and components, determine the libraries it uses and what bits of code could be removed assuming it will only run on this system (e.g., Linux) and then to update it to C++ and change the option parsing to use Boost.

| Task | Duration [min] | avg. Power [W] | Energy [Wh] | Idle power | Excess energy [Wh] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code ingestion and analysis | 12 | 160 | 30 | 122 | 5.6 |

| Remove BladeRF and extra architectures | 57 (34) | 165.6 | 170 (93.8) | 122 | 64.1 (32.9) |

| Convert the project to use C++ compiler | 100 | 180.3 | 320 | 122 | 157.3 |

Introduce Boost's program_options |

175 | 185.2 | 550 | 120 | 200 |

Note that the energy values presented in the 4th column are taken from the database directly, rather than being computed from the average power draw. Exception: The bracketed values correspond to a hypothetical value that would be obtained if the duration was adapted to the bracketed time provided in the corresponding row.

Installation & configuration - an aside

Installation via curl + Bash went off without a hitch - though I think this pipeline should be avoided as it's a one-liner black-box installation.

The documentation is sufficiently simple for a fast set-up. The following configuration is stored as opencode.json in $HOME/.config/opencode:

1{

2 "$schema": "https://opencode.ai/config.json",

3 "theme":"catpuccin",

4 "autoupdate":false,

5 "provider": {

6 "lmstudio": {

7 "npm": "@ai-sdk/openai-compatible",

8 "name": "LM Studio (local)",

9 "options": {

10 "baseURL": "http://127.0.0.1:1234/v1"

11 },

12 "models": {

13 "qwen/qwen3-coder-30b": {

14 "name": "Qwen3 coder 30B (local)",

15 "tools":true

16 },

17 "openai/gpt-oss-20b": {

18 "name": "OpenAI GPT OSS 20B (local)",

19 "tools":true

20 }

21 }

22 }

23 }

24}

Note that for now I'm using the schema as it is stored online. The only handiwork here are the two models whose IDs need to correspond to the way they are stored in LM studio (e.g. qwen/qwen3-coder-30b).

The model server built into LMS just needs to be enabled in the Developer window. Once a model is loaded its API identifier can be copied from the "API Usage" field of the "Info" tab.

The default parameters of the model for my system were resulting in frequent so-called doom loops. This required an hour or so of adjustments to the model. Specifically:

- Ensure that the prompt is using the default Jinja template and not the manual ChatML selection.

- Up the context length to 54253 tokens

- Increase the GPU offload to 30/48

- Enable offloading of the KV cache to GPU memory

- Enable "Keep model in memory"

- Enable "Try mmap()" (likely useless)

- Increase the number of experts from 8 (default) to 16

- Force model expert weights onto CPU to reduce the strain on GPU memory due to the larger context length.

- Disable "Flash Attention"

This results in the model using up to 9.3 of the 12 GiB of VRAM, thus still leaving room for improvement.

Analysis

The initialisation step kicked off using the built-in /init prompt shortcut completes in 7 minutes. A follow-up query about the programming language used requires 1 1/2 minutes to yield the correct result. While the identification of the libraries used in the project takes only 1/2 min it misidentifies pkg-config as a library and requires explicit instructions to correct the error.

Upon request the tool confirms that bladeRF and extra architectures for macOS and FreeBSD can be removed without impacting functionality.

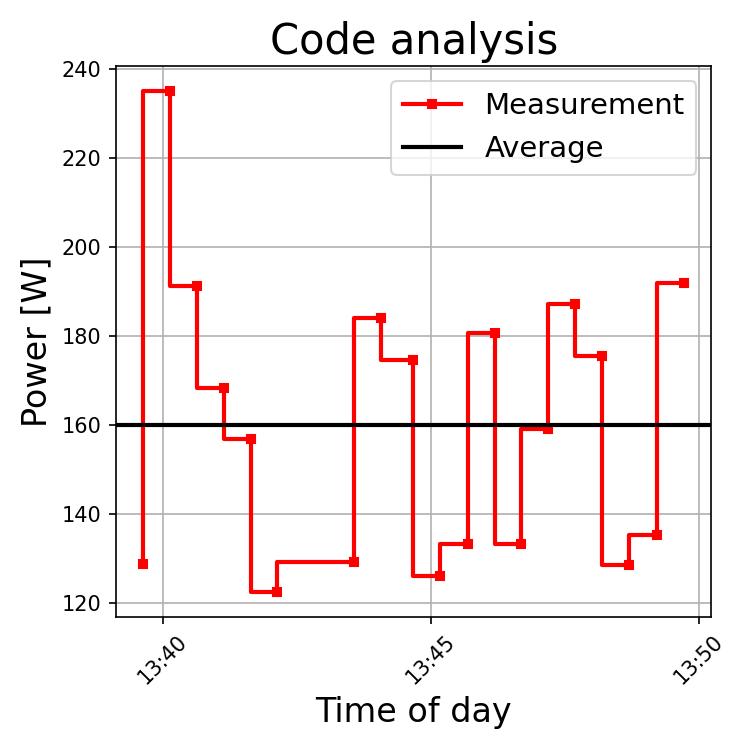

We see in the above image that the power draw of the system is rather non-uniform. Phases of high energy use indicate the use of the GPU and thus the LLM, whereas subsequent phases are due to OpenCodes processing. Phases with a power draw of around 122 [W] indicate that the system is idling. These are generally due to me reading the responses or performing additional checks by hand. The average power draw here is 160 [W], scaled with time this would yield ~27 [Wh] of energy consumed within the 12 minutes.

Summary: The initial exploration of the project's code went off without a hitch and required ~12 [min]. It identified superfluous architectures and code correctly, but misidentified pkg-config as a library of the project, which had to be corrected manually.

Compared to the manual analysis this is a reduction by a factor of 6! One could try and argue that the directions regarding bladeRF and additional architectures require a-priori knowledge of the code, but the request to analyse the dependencies of the code lists it as an optional dependency.

Trimming the fat

Next up is the removal of BladeRF and of the handling of FreeBSD and macOS.

Instructing OC to proceed with the removals suggested in the analysis step while keeping all required libraries included removed extra architectures and bladeRF from CMake files only! This takes 4 [min] to complete and requires an additional 9 [min] to clean up the source code after re-checking it for an additional 10 [min] and a further 4 [min] to identify and remove files that are not needed anymore by the project.

The modifications result in a code that does not compile! Instructing OC to compile the code results in it fixing the issue in an additional 5 [min]. This motivates the inquiry about how the code can be tested. And after instructing the tool to drop Kaminsky de-biasing a short, working test command is obtained within 6 [min]. Instructing the tool to commit this test to its AGENTS.md file requires an additional 5 [min]!

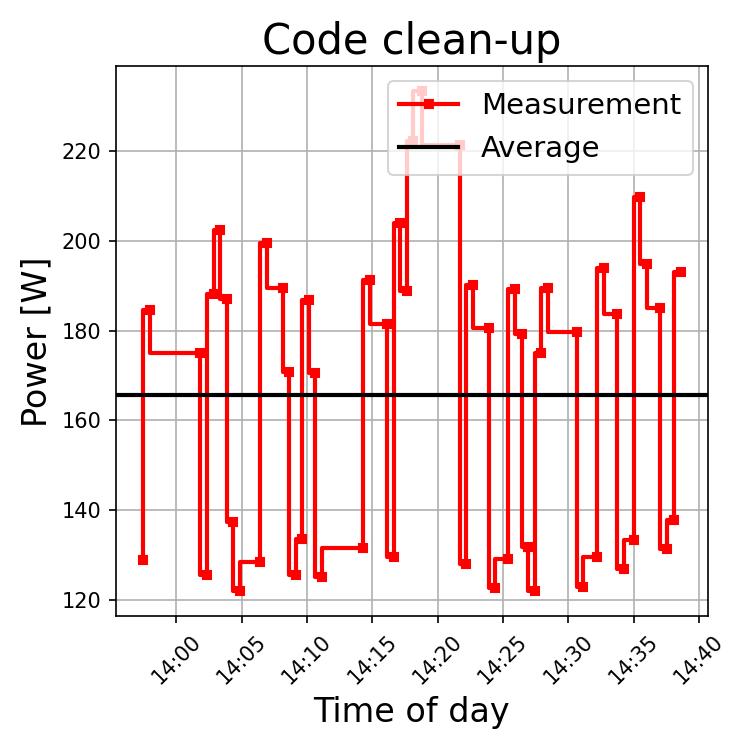

Again, we observe a very jagged power draw with short bursts due to the use of the LLM that are followed by plateaus of OpenCode use. Since the latter runs solely on the CPU it does not result in very high power requirements due to the powersave governor. Here we can also obtain times (e.g. starting at 14:05) of elevated power draw preceding the use of the LLM. These likely correspond to tool invocations whose output is then processed in the subsequent LLM call. Due to the frequent but short use of the LLM the mean power draw is 165.6 [W] and largely due to the OpenCode agent.

Summary: The simple act of removing unneeded code from the build process and the source files required a total of 34 [min] to accomplish, with bits of superfluous code still remaining in the CMake files. The time required to determine and codify a proper test - something that is suggested in the README - is 11 [min].Thus the productive time required to perform the task was 45 [min], more than a factor of 3x larger than the manual removal. Note that the time required to check the work and write instructions is not explicitly mentioned here. The total time required for this step was 57 [min]!

Converting to C++

Requesting a suggestion of the steps to be taken to convert the code to C++ via "The goal is to convert the project from C to C++ without changing functionality. Which steps should be taken next to accomplish this?" results in the tool locking into object-oriented programming paradigm and immediately proceeding to modify the code. This forces a roll-back and a wasted 28 [min].

"I do not wish to convert the code to conform to object-oriented programming structure, only to convert it from C to C++ while keeping the structure the same. Suggest steps required to do this but do not modify the source."

Suggests a reasonable list of changes, but proceeding with those leads the tool on an excursion to the system's include directory after which it took around 5 [min] to return to the correct project directory. The result of this meandering: Only 2 source files are correctly renamed to *.cpp and after 37 [min] we are left with a code that does not compile.

Letting OC try to fix the compilation issues takes an additional 18 [min] with no success and only after explicitly instructing the tool to "*Rename all *.c files in the project into .cpp files and change @CMakeLists.txt and @src/CMakeLists.txt accordingly." does the resulting code compile.

What is not obvious from the printed output is that OC creates a lot of superfluous CMake and Make files within the project at this point and uses those instead of the existing build process!

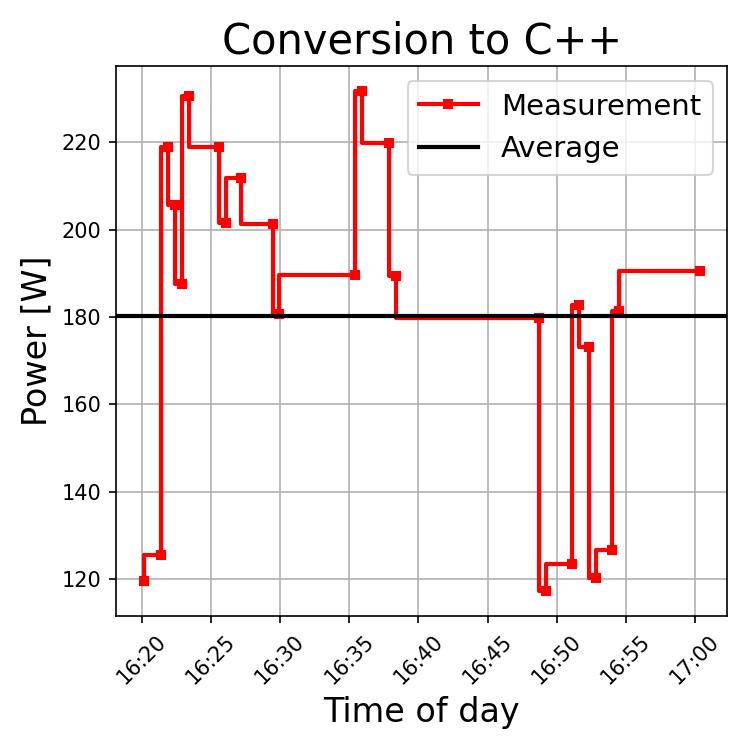

The skyline of power in this stage is dominated by the GPU and thus the LLM. The time span between ~16:37 and 16:47 roughly corresponds to the time the agent got stuck in a loop. The more frequent use of the model by OpenCode is reflected in the 180.3 [W] mean power draw.

Summary: Overall the simple conversion from C to C++ required 100 [min] with OC + LMS. This can probably be reduced to ~25 min, seeing as the renaming process and update of CMakeLists from an explicit instruction required only 5 [min]. A lot of time is wasted here by the tool trying to do a programming paradigm change and building a parallel build process.

Introducing Boost

This process was a prolonged mess, so I'm only providing the summary:

Upon request the tool correctly identifies the 3 functions responsible for user input and the command line help and provides suggestions on how to replace them using Boost.

Instructing OC to replace the identified functions using program_options and providing two source files from a different project as references for the implementation results in the tool taking 56 minutes to update the code. The result does not compile.

Identifying now-obsolete functions and trying to remove them results in doom loops and more than 1h of time spent to fix compilation issues. The issue at hand: A missing inclusion of the Boost library in the CMake files of the project. This issue likely originates from the parallel build process that OC has created in the previous step. Instructing it to remove superfluous files and directories fixes the compilation issue because the tool now includes the library in the appropriate CMake files, but that is not what was requested! The overall time spent on this stage alone is 175 [min].

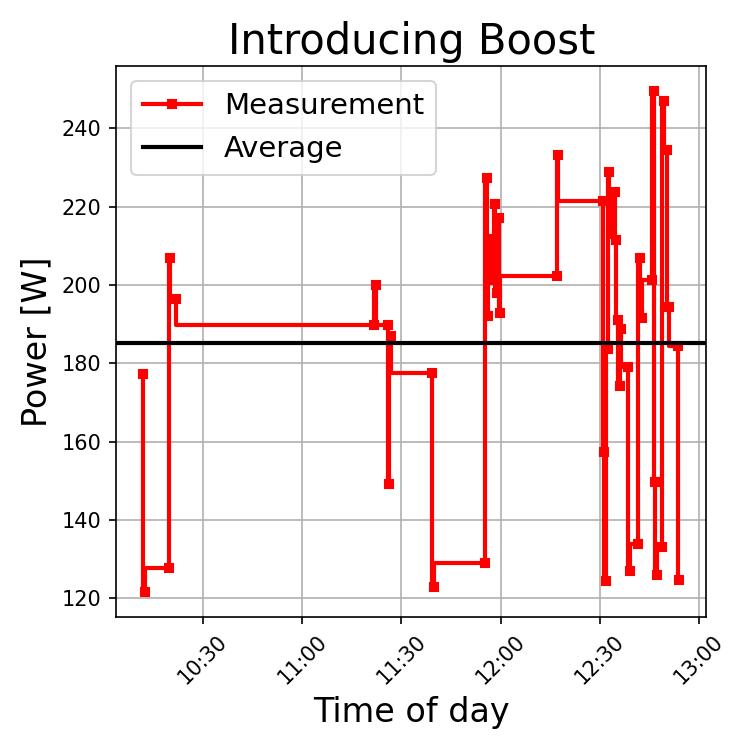

This step, too, is dominated by the LLM use. Arguably more than the conversion step above. We see this in the prolonged periods of above-average power draw, as well as with by way of the mean power requirement being 185 [W].

Summary and Conclusions

The minimal requirement to update the code from C to C++ and remove unused libraries and code has been achieved successfully using OpenCode and LM Studio with Qwen3 coder 30B model in 169 [min], or 2.82 hours. For the entirety of this time the PC was running at an average of 160 to 185 [W], resulting in an overall energy consumption of 520 [Wh].

The optional but desireable goal of introducing Boost's program_options library to handle runtime parameters hoping to reduce the amount of code was not successful. While the changes required an additional 175 [min], even when an explicit example of how the library is to be used was provided, the resulting code compiles but fails at runtime. Functions made obsolete by the inclusion of Boost still remain in the code, as do superfluous bits in CMakeLists.txt. Again, at an average power draw of 185 [W] the total energy required for this step was 550 [Wh].

The process of conversion required manual intervention twice, to prevent the tool from changing the programming paradigm of the code and to terminate an apparent doom loop. In the meantime instead of reducing the amount of code the tool introduced more than 10 superfluous CMake files to the repository and committed (unprompted) the temporarybuild directory, too. The introduction of Boost, even given the same example I used when manually rewriting the code, required an additional 2.9 hours to yield a dysfunctional code. The total energy required to reach this point was 1070 [Wh], or 1.07 [kWh]. This is surprisingly close to the "median day" value of \(\sim 1.3 [kWh]\) obtained by Simon Couch for Claude code, though I hope his projects were more complex and successful!

While the update of the project code could be achieved with LLMAC the resulting code base is bloated and barely functional. The process required multiple interventions to terminate doom loops. The entire process could be made more efficient by providing more constrained (read: longer) instructions.

Subjective observations

Now to turn to the subjective observations of working with an LLM, or: "How it feels to work with an LLM." Since the individual steps required to achieve the minimum requirement of the project were on par with or longer than a manual rewrite I'd expect some benefit w.r.t. time if I had better hardware (e.g. 24 GiB VRAM) and the coding agent itself was faster. As it stands using OpenCode to port the small code base from C to C++ does not reduce the time required to achieve the goal. Moreover because the tool constantly requires supervision or a well-prepared and constrained specification of the tasks, lest it tries to modify the source code without being requested to do so, it is also not really possible to leave it to its own devices for longer stretches of time. With output coming in every ~2-5 minutes and some inputs resulting in wait times of 10+ minutes the intensity of the interaction with the tool is not sufficiently high to support concentrated work for a prolonged period of time. As such the process of LLMAC promotes concentration-dissipation by way of giving me the choice of either twiddling my thumbs doing nothing while the tool tries to accomplish the task, or setting up a secondary task to work on in parallel (like writing this article!). This suggests that one is more productive because one's working on two tasks in parallel. To me this is an illusion since this parallel processing tends to yield half-baked results!

In contrast, the manual update of the source code was spent mostly with some degree of concentration on the tasks at hand with far fewer impulses to read the news or check BlueSky.

This propensity for concentration-dissipation could be mitigated by a more active exchange with the tool. That will require faster hardware and more constrained and therefore longer prompts, which in turn requires more VRAM and also increase the time required to formulate the proper prompt. One might claim that the added downtime allows the developer to focus on other parts of the code or other tasks that need to be done. Sadly the need for constant supervision of the tool puts a limit on the complexity of tasks that can be accomplished in parallel since prolonged concentrated work is not possible. I could see these tools being useful when dealing with a lot of smaller unrelated changes - tasks that do not require a lot of thought.

Conclusions, reflections and the future

Overall the conversion of the simple code base of rtl-entropy from scratch from C to C++ took 3.6 hours to achieve by hand, of which the analysis of the code base required a large chunk (72 [min]). Analysis was only overshadowed by the modification of the code to use Boost - a task limited by editing speed. In contrast, the use of LLMAC to achieve similar results required a grand total of 5.73 hours (5.37 if we're generous), of which the vast of time was spent trying to use Boost's program options library to parse user input and provide help.

In the following table the time for each step and the energy required are summarised, with the higher value highlighted for each step

| Task | Human duration [min] | Tool duration [min] | Human energy [Wh] | Tool energy [Wh] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code ingestion and analysis | 72 | 12 | 157.8 | 30 |

| Remove BladeRF and extra architectures | 14 | 57 | 31.7 | 170 |

| Convert the project to use C++ compiler | 46 | 100 | 104.1 | 320 |

Introduce Boost's program_options |

88 | 175 | 183.3 | 550 |

| Total | 220 | 344 | 476,9 | 1070 |

Overall the manual update used roughly 477 [Wh] of energy accomplishing the result in \(\sim 3.7\) hours , whereas the agentic update needed 1070 [Wh] to accomplish the same task with increased supervision in 5.7 hours.

The conclusion I am therefore forced to draw is that LLMAC in the set-up considered here is not worth it, since it reduces neither the time-to-solution nor the energy-to-solution. In fact it increases both significantly (1.56x for time and 2.24x for energy)! This is notwithstanding the fact that the manual rewrite results in a functioning code, whereas the tool-assisted one does not. The only benefit I observe here is during the anaylsis stage, which is accelerated significantly by the use of the tools.

Additionally there is a high likelihood of interference when working on the same code by hand and using LLMAC since the tool is not guaranteed to stick to a designated part of the source directory. It does not even stick to the project directory! This issue could be circumvented by having two copies of the code on the system with the user and the tool working on their respective copy. For me that is a recipe for confusion later on, but feasible in principle if the code base is manageable.

Caveats and their effects

The exploration described here was performed for a small code base with little a-priori knowledge on my part. Hence it seemed fitting to compare how I deal with the task at hand, from exploration to update and testing, to the way this process would be accomplished with LLMAC. This meant that I tried adding as little of the knowledge gained from the manual rewrite to the tool-assisted process. The loops that occurred at various stages have been resolved by introducing additional knowledge to constrain the range of checks and explorations the tool could try. Thus the overall conversion process using LLMAC can probably be sped up if one is already sufficiently familiar with the code to direct the tool with pinpoint precision and provide enough constraints to avoid looping. The comparison was also done with as little intervention into the agents progress as I could get away with. A more active involvement could potentially reduce the amount of errors made and thus the overall time to solution.

It is worth noting that querying the model used here with LMS requires roughly 35 seconds to respond to "What is the formula to compute an unbiased estimator of the sample autocorrelation?" whereas ChatGPT achieves the same in ~20 seconds, corresponding to a speed-up of about 1.75x. Assuming no change in quality (a strong assumption) this could be sufficient to achieve time-parity between manual and agentic conversion of the code! Assuming further a much higher quality/larger context size etc. of the external model I can imagine a reduction in the time required to obtain the desired solution!

For an ab-initio conversion of an unfamiliar code base from C to C++ the use of OpenCode with LMS saves neither time nor energy. It takes slightly longer to achieve the minimal requirement with LLMAC than if the process is performed by hand, though we could hit parity if we're charitable. Since the system is running with a fairly high load for the majority of the time the energy consumed is significantly higher. Every step of the update uses ~170 [W] when performed using LLMAC and ~120 [W] when done manually. The energy budget of the manual rewrite is dictated by the system's idle power draw and can be significantly lower. For instance: performing the same task but using a RaspberryPi 5 instead of the Ryzen system would reduce the idle power draw to ~54 [W] and therefore require only 198 [Wh] of energy, catapulting the human-powered rewrite ahead in energy-efficiency by a factor of 5.4!

The future

I am turning this into a little series on the effectiveness and efficiency of locally-run models in software development. It'll be interesting to tune the parameters of the model further to utilise the available resources to their fullest. I hope this will reduce the time-to-solution while simultaneously improving the quality. Another variation to consider will be the constraints on the inputs to prevent OpenCode excursions.

For a future comparison between various models (e.g. GPT OSS, Devstral etc.) using the same simple task a more rigorous set of fixed queries and instructions would be required. While the RNG of the model can be seeded in LMS, the inputs are arbitrary and will make a comparison of various models more difficult.

Final thoughts

From the observations presented here LLMAC is not meaningful to me, neither w.r.t. time nor energy. The former can likely be substantially reduced, which would make the tools attractive to save time. I expect such time saving to be accompanied by a corresponding increase in energy used, though. Given the observations and the brief comparison of generation speed to ChatGPT (c.f. Caveats and their effects) I expect an observable speed-up of the work, but not by a factor of 10.

The low-intensity of the work when using LLMAC facilitates, for me, loss of concentration, which in turn results in less precise commands to the tool and a higher likelihood of unintended consequences and the need for extra work to fix such consequences.